Advanced Wing Chun Philosophy

Fighting a Stronger Opponent

Pragmatic philosophy of Martial Arts

Introduction

Philosophy of Martial Arts... We are conditioned to think of it in terms of a harmony, meditation, of zen with its paradoxical questions, of In and Yang...

Forget about it.

Long time ago, when I came to my very first Tai Chi school... No, not like that. First of all, I already had some prior Karate and kung fu training, and second - it was not the first Tai Chi school - it was like twentieth.

See, when I decided to learn Tai Chi, I simply downloaded a list of local schools and went on by visiting them, one after another. Sometimes, I saw errors in what students did: when you study long enough, even in a different school, it is easy.

Sometimes I didn't like the teacher as a person, or the room where they practiced, or...

Anyway, here is the reason I chose that particular school: when I asked the teacher about "energy", he started to laugh.

Let me explain. For a teacher, a conversation with a newcomer is always a bit of a show. A chance to present the school, and let's face it - a chance to brag, just a little bit. And when a newcomer asks about the "energy", how to resist telling a mystical story or two, to explain, how good is this particular school in energy manipulations, and how good are you, as a teacher?

He laughed instead.

"Energy", he said, "all these stars, octograms and energy channels, it all is for Europeans. You are so romantic! Hah! While Chinese are practical folks, and instead of stars and thin vibrations, we rely on gravity, inertia and human physiology".

This, I thought, is something to think about. And then I asked him to show me his skills. Well... I flew, my back forward, for about four meters, and stopped only when I hit the wall.

So much about philosophy.

What we, "romantic Europeans" keep forgetting is that Martial comes first, and only then comes "Art". You meditate instead of practicing - you die, this is that simple. Just ask yourself a question: what kind of philosophy should one expect from a live-or-die art of 16th century? Astrology? Thin vibrations? Hm...

Also, it should be simple. The second time my Tai Chi teacher laughed at me, was when I asked him about Bagua kung fu. According to what I knew, they used astrology and octagons, and some other semi-mathematical staff.

"Listen", the teacher said, "Most of them were not even able to read! What astrology are you talking about?"

Yet, Bagua works in martial confrontations, and works well.

In this book, I am going to explain philosophy of one particular style, the Wing Chun. However, you can apply same kind of logic to other styles, to figure out, what REALLY lies behind the rules of that style. Ans yes, I am not going to be talking about astrology and energy channels.

Why should we bother?

"I do not need any philosophy. I do what my teacher tells me to do, and as he fights well, so will I, with time".

This is true and not true in the same time.

First of all, there is a difference between a Teacher and a Master. I know great fighters that are not able to teach, and I know fighters that are quite mediocre yet they teach and teach well. Those are two different gifts. Yes, sometimes a person can both fight and teach, then he is a Great Teacher, but in most cases it is not so. Therefore, the fact that your teacher is good does not necessarily mean he can teach you.

Even if your teacher is good and you study long enough, you will have to figure the philosophy of the style you practice, even without learning it explicitly. But - it will take longer. Longer.

"How often and how long should I practice Martial Arts?" a student once asked.

"Three times a day, eight hours each", the teacher answered.

This is a big problem of a modern society: we are not ready to abandon our lifes and to spend the next ten years in a Shaolin temple. We want to have two classes a week, something from hour and half to two hours long, and there have to be a shower in the dojo, too.

Will you have enough practice to learn the philosophy of a style? Probably not.

By the way, Oyama, the founder of Kyokushin Karate, got his black belt when he was thirteen years old: do you think he practiced twice a week? Nope.

This is one reason you need to learn philosophy as opposed to "kind of figuring it out".

The second reason is a bit more complex. It is like the difference between the child and an adult. When you show a magical trick, a child cries "Wow! How'd you do that?!" while an adult just says "Wow!". Lack of curiosity.

See, when you are REALLY studying something, you need to be involved - hundred percent. In NLP it is called a "state of passionate commitment". You MUST WANT to learn what is behind the kicks and punches, or you will never evolve from "mediocre" to "excellent".

Some time ago I studied Aikido on a seminar in USA. For the particular exercise, I paired up with a man wearing a hakama, which means he had a black belt. The teacher said "ok, nage (attacker) attacks with dzuki (a karate term for straight punch with the fist)". And then I saw the strangest and weirdest thing: my opponent brought his fist towards his shoulder and punched me with the palm's side of it.

Chances are, my description isn't clear, let me rephrase: he did a classical "girls' punch", not the "legal age" girls', but - have you ever seen five years old children fighting? That's right. Hakama. The black belt.

"Excuse me", I said. "This isn't exactly a dzuki."

"Well", he went, "I never studied karate, so I don't really know how to do it properly".

The "black belt" means that the man spent significant part of his life studying aikido, which, let's face it, is a set of techniques to defend against karate. And he still does not know what he is supposed to be defending against. What a waste of time!

Curiosity would speed up his learning and, frankly, unless he exercises some curiosity, he never learns anything.

And finally, the third reason to learn philosophy, the most important one and the one people always miss. See, IF YOU KNOW WHAT THIS MARTIAL STYLE IS ABOUT, YOU CAN RECONSTRUCT IT. Let me explain.

First of all, your teacher is not always watching you, he has other students too. So you will be making mistakes, until he notices, wouldn't it be better if you do it correct way from the very beginning? And yes, it is possible. Well, mostly.

Second, sometimes your teacher is wrong. Take me, for example. I came to Wing Chun from Tai Chi, and if I was asked to teach Wing Chun, I'd tell my student to always turn around on the middle point of the sole. Because in Tai Chi, a great deal of attention is paid to balance. We move the body down - our hands should go up. We push with one hand - we pull with another. The path, so to speak, lies in the middle, including spinning on the middle of the sole.

Shouldn't it be the same for Wing Chun? The answer is NO.

Let's take a closer look at this particular example, and let's do it from the point of view of philosophy. I am going to outline Wing Chun philosophy later in this book, for now, we are going to only use the following statement: "the essence of Wing Chun philosophy is AGRESSION". So much for "Wing Chun was created by a women" (so what?) and "it is not challenging at all" (it challenges your spirit like no other Martial Art does).

Aggression. Attack. That's right, we always attack in Wing Chun. We go forward, or forward and sideways. We do not retreat.

Now back to our question. On the following picture you can see a projection of a person's sole. Due to some strange reason (perhaps, there is more than one opponent), the person faces the wrong direction, so he has to turn 180 degrees towards the (new) opponent.

Now, tibia, the cannon bone, is perpendicular to the ground, more or less, and it is attached to the foot right above the heel. While the "Middle of the sole" point that is used in Tai Chi, is a bit to the front. As the result, if we turn on our heels, our body's central line will not move. While if we turn on the middle of the sole, our body moves back.

But Wing Chun never moves back! So what is the point we spin around on ? Heels, and only heels. Which we have just concluded from a rather abstract "we always move forward" statement.

Presuppositions. What we take for granted.

Let's take a look at a hypothetical model of Martial Arts being practiced on an island in the ocean far, far away. The Ultimate Objective of these Arts (there are, of course, multiple schools each believing in its superiority) is to touch the ceiling of a dojo. That's right, why not?

Now, as I mentioned, there are few schools. One, the style called "crouching pig", uses ladder. This technique allows the adepts to reliably touch the ceiling, so it is considered the best... by all people practicing it.

Their competitors and foes, the style of "hidden skunk", consider using ladder a form of cheating. What if you don't have a ladder when you need one? What if it is stolen by your enemy? What if the floor isn't even enough to set it?

So they jump.

Jumping only works on certain types of ceilings (low ones), but it is fast, and it keeps people practicing the style in a great shape.

There are also few minor styles, that... Anyway, I think you got the picture.

Did you?

Well then, let me ask you a question: why do they need to touch the ceiling?

See, as those Martial Arts are centuries old, and the island is not very advanced in terms of writing, they do not remember! Even oldest masters have no idea, which means they tell nice stories and spiritual metaphors. Were they painting the ceiling, long time ago? Picking up fruits? Maybe a mouse died there and someone had to remove the source of smell?

We do not know anymore.

Another question: why ladder?

No idea. Maybe the first Master was injured and couldn't jump.

Or maybe he was selling ladders. What a mystery!

Now back to Martial Arts of our world. You know that wrestlers are very dangerous opponents. And if you doubt it, look at "full contact - no rules" championships: wrestlers are always among the winners. Yet, Wing Chun almost never wrestles - why?

Boxers jump. No, they are not trying to touch the ceiling, but they do jump. Just like that, up-down, right - left... Why? And if it is good for boxers then why wrestlers do not do it? Also, boxers duck, in order to evade attacks, which you will never see in Wing Chun. Is there a reason for it, or is it like with our imaginary island, just a tradition that no one can trace back to its roots?

It is very important to know the answers to these questions. First of all, it will help you to choose the style you want to study. Second, which is the reason this book was written: if you know WHY, you usually can figure out HOW. See the example with spinning on the heels above.

Rule 1: You do not quit.

It is very important to realize, that each martial style has its limitations and that these limitations rely on some PRESUPPOSITIONS (something we presume to be given). For example, a fencer would always assume that in a martial situation he will have a sword. Which may or may not be true.

It is even more important to understand, that if you do not practice these presuppositions, if it is not how you operate in a fight - you are at a huge disadvantage. Because you will have to come up with a replacement, under a stress, right there, in the middle of a fight. Should I jump? Should I duck? Should I run?

So, all these boring words below, they are more important than techniques.

As a warm up, let's examine boxing technique, keeping in mind that tools they use (ladder) are most likely related to their goals and limitations. By the way, boxers are very unpleasant opponents, they are usually fast and strong, so - I am not criticizing them, I am just trying to explain why they do things their way and Wing Chun does them differently.

First of all - they wear gloves - why?

Because boxing is, to a large extend, show-oriented. They want to show (to the public) their techniques, and to do it, they have to last longer than few seconds; few seconds, by the way, is a duration of an average martial confrontation, provided you have no gloves.

Also, a real martial situation is an exception. How often does an average person fight for his life? While boxing is a career. Day after day, year after year they fight for victory, which means they have to somehow survive through these years. There come gloves.

So, what are the presuppositions of boxing? First of all "there are rules". As simple as it is, this presupposition makes a huge difference. Rules demand that you and your opponent wear gloves. Rules state that both of you must belong to the same weight range. Rules prohibit you from using kicks, elbows and head, as well as from attacking below the belt line.

Also, there is a general rule that says something like "your opponent does not have a sword".

Is it always like that? No. You can use legs in karate, though you still can not kick your opponent in the groins. Some styles do work against an armed opponent. Some grab opponent's hands or clothes - a behavior impossible in boxing, as they wear gloves!

But generally, every competition-oriented school has rules. While in a life-or-death situation the only rule states: "no rules".

In Wing Chun there are no rules. Of course, in a class students do not kick each other in the groins, they "show" the kick but stop before the contact happens. Same with striking in the opponent's eyes: we show the intention, but we always keep in mind that "good opponents are hard to find", so we do our best to preserve them for future use. Yet, Wing Chun students practice all "non-sportive" staff.

THERE ARE NO RULES! This is a first presupposition of Wing Chun... and yet, in Wing Chun we do not, usually, do wrestling? Why?

Because there are other presuppositions, that make us to apply additional limitations. Let's go to boxing example again.

If you practice Martial Arts long enough, you are being constantly told that "the best fight is the one that never happened". So... Can a boxer run away? Yes and no.

Think about it. Most street fights are for nothing, and if you managed to run away, you did well. Of course, there are situations, when you have to defend your family or simply someone who can not defend themselves, and in that case you can not run. But in boxing if you left the ring, you lost, and yet you still can leave, I mean you can stop the fight.

Which shows us a huge difference between the fight in a real life and on the ring.

On the ring, you can give up, and the moment you do it, the fight stops. In the real life... Well... Some animals have "submission postures", for example, the dog falls on its back, exposing its throat: "I give up, spare me". Humans do not have it, period. So if you fight against bunch of criminals, and you have injured few in process, can you say "ok, I quit"? No, because THEY wouldn't stop.

So the second presupposition accepted by ALL combat (as opposed to competition) oriented schools is "you can not quit". You fight until either you or your opponents are unconscious or worse, something like that.

As Wing Chun accepts that presupposition, let's think of the way it changes our fighting style. "He" punches, you punch in response. In a bar fight (which is NOT a place to fight, by the way. A bar fight is not a life and death one, and if you study Martial Arts, you shouldn't fight in bars anyway). Anyway, in a bar fight fighters usually stop at that point, looking at each other.

Which is wrong. As you can not quit, you should continue fighting, until your opponent is down.

This is exactly what you see in Wing Chun, punch after punch, delivered at a maximum speed. As one of my teachers once joked, the judge asks "what happened" and a witness says "Well, I do not know who started it, your honor, but than that gentlemen punched his opponent in the face twenty times". Well... Do not fight in bars.

As you can see, we did it again; we took a presupposition (you do not quit) and we DERIVED a proper behavior (keep punching). Wing Chun students often ask "what should I do after I did this three punches, should I wait / step back / re-balance?" No. Keep going, this is a Wing Chun way. You stop, he suddenly remembers that he is a professional boxer, punches you once, and you are dead. Think about it.

You do not have space.

Our first presupposition was "you do not quit". This one says "you do not have space". It seems that all presuppositions of Wing Chun are negations. The reason is, and it is a good idea to ALWAYS keep it in mind, that Wing Chun is a style for a weak small person fighting the big mean one. Can the small one win? And why should we presume we are smaller and weaker?

Because, if you want to be stronger, you choose wrestling, and if you want to be bigger, you choose sumo. Or, to put it differently, you usually have no problem fighting someone who is weaker. Fighting a stronger one is another story. And unfortunately, sometimes you simply can not run.

OK, back to boxers. Boxers fight at the ring, a fixed room that allows sufficient space for maneuver while not allowing one of them to run away. Very convenient.

Unfortunately, in the real life situation everything is different. Can you jump in circles in the elevator? Probably not. On the broken glass? No. Knee-deep in the mud?

No.

Also, and for the same reason, you can not tilt your body. Not in the elevator. Not in the crowd. Not in the bushes, unless you don't mind accidentally loosing your eye.

Also, can you do wrestling - not a close range wrestling, but all those "hip throw", "two handed shoulder throw" and so on? Sorry to say that, but it doesn't work in an elevator.

So: "you do not have space". In Wing Chun, the back is always straight, because bending is against this presupposition. We move forward by small well-controlled steps, no jumps. The heel goes down first, so that the sole of a front foot does not slide forward. Same reason: if the floor is not even, you will trip and fall.

Also, in Wing Chun we do not go back. In addition to "you don't quit" that suggests aggression, but the original reason for it is simple: we may not have space behind us! While in front of us there is some space, all we have to do is removing our opponent from it. Very straightforward.

You are weaker.

In a "Lethal Weapon - 3" one of the characters is a (bad) Chinese guy with excellent kung fu knowledge. He is a leader of a gang and when two of his subordinates fail, he kills them with his bare hands. They were strong and agressive men, yet they could do nothing, he moved as a perfect killing machine, flawless and efficient.

Often, Martial Arts students think that when they learn "kung fu", they will become like that.

Forget it.

Now, don't take me wrong, the more you learn, the better you perform in a combat situation. Anyone can defeat the three year old boy, right? Well... almost anyone. If you practice, you will be able to fight the unprepared person as easy as you would fight a child.

Is it why you practice - to fight unprepared people?

Well, bad news, your opponents are going to be (most likely) prepared. Boxing? Fast and VERY strong punches. Wrestling? Unstoppable, and the feeling is, they are made of iron. Karate? In Kyokushin, they have an exercise: they break helve of a shovel against the students' shin... And the worse thing that can happen to you is when you strike your opponent, just to discover to your horror that he does not collapse! Help! What should I do?!

No mater how strong you are, you MUST assume your opponent is stronger. You might grow old some day. Or you might have food poisoning. Or maybe you just have had another fight, you won but you are tired now. Or there can simply be five of them.

In any case, if you do not have proper program in your brain, you will spend time trying to figure out what to do. Do you have time for that in a martial situation?

You do not have time.

Let's examine the boxer's technique again. He and his opponent perform what looks like a dance. They jump, they do feints, they tilt their body to the side an immediately to the other... while standing two meters apart. In karate, there is a special term "ma-ae", the effective distance. In other words, if you are outside your opponent's range he can not attack you in one move, he'll have to come closer, first.

So why do they jump while being at a safe distance from the opponent?

Mostly because in boxing the punch begins with the leg, so when the leg is like a spring (up - down), it is possible to deliver a punch... and as they constantly shift the weight, it is also hard to predict.

And notice how they circle around each other? Circle after circle, until one of them makes a slight mistake. It is a very convenient way to rest. See, if they simply stop, a referee will punish them for being inactive. While as they make all these circles, they ARE active, yet, they use that time to regain their strength.

The only problem with that approach is... Imagine a street fight. Little jump forward. Jump back immediately. Half-step to the right - step to the left. Tilting the body right, tilting the body left. And right again...

While behind your opponent's back his friends are killing your family. Now, do you really have time for all this dancing? No.

A popular street fighting technique when you are alone and there are few opponents, is to turn and run. If they do not run after you, good, YOU WON. If they do - run for a while, then turn around and knock down the one running right behind you. One. And you have to finish the fight by the time others catch up. This way you can defeat them one by one, but to do it you have to be able to win FAST.

That was the second reason to keep your fights as short as you can. Here is the third one. When you interact with your opponent-to-be, verbally, you need to make some estimations. Who he is, how to deal with him, can you talk your way out of the situation, and so on. Take your time, so to speak; the best fight is the one that never happened.

But lets say you realize that the fight is impossible to avoid. So you start, and you have to do maximum damage to your opponent, before he pulls himself together and begins responding. Ideally, you knock him down with the first strike.

It is also possible that he attacks first. Most people, even ones with some martial training, punch few times and stop. Just for a moment. It is like a reconnaissance, like those very first "punch-punch" in boxing, like saying "hi". It is our monkey inheritance: "I am stronger, here is your chance to run away".

They, most of them, expect the same from you. And if you charge at full speed and strength instead: ten, twenty, forty punches - they will not be ready.

Now, let me repeat: we assume we are weaker. We are weaker than five people running behind us. We are weaker than five people that are about to kill our family. We are even weaker than that psycho in a bar. It means, in the same time (say, in five seconds) of a fair fight they will do you more damage than you do to them. Whatever time we waste - is for THEIR advantage; do not waste any.

You will loose.

Closely related to "you are weaker" presupposition, this one still deserves being listed separately. We all know what to do when we win. What to do when we are loosing it? That same situation, when you are cornered and there are five of them...

We fight. Fight not to win, but to do as much damage as we can. Why? Because we do not want to spend time figuring out if we should quit. We never quit.

As I mentioned above, people are not very good under the stress when they do not know what to do. And as you can not take a break in order to think (during a fight!), you better have your answers ready BEFORE you start fighting.

One of the reasons to continue is, of course, that you should keep fighting because miracles happen, and a dozen of navy seals might happen to be passing by that same alley in that same time... But hoping something like that happens is nothing but stupid.

To make our little puzzle more complex: you need to always fight as if you are about to die, you know it and you have accepted it. In other words, in order to make our actions more efficient, we intentionally sacrifice our self-preservation instinct.

Bring all presuppositions together, and you will see why. You are weaker, no space to run, no time to loose and you can not quit, which means - continue fighting no mater what. See how self-preservation fits in this picture? No? That's because it does not.

This approach affects Wing Chun techniques greatly. For example, a common mistake students

make is pulling the hand back after performing a blocking technique.

If that student applied our presuppositions, he would have immediately seen that:

a) We do not retreat / We do not have space. Indeed, if you move your hand back,

your opponent will move forward, after all, he wants to occupy YOUR space same way

you want to occupy his.

b) We do not have time. What exactly we moved our hand back for? As long as it goes back,

it does not strike, so it is a time wasted, pure and straightforward.

Great, but if the hand does not go back, should it go forward? Yes. And what if an opponent uses the opening to strike YOU?

We do not care, we will loose anyway. All we care is opponent's face.

For the same reason, Wing Chun focuses on attacks rather than on defenses. Say, we punch. If our hand finds its way to opponent's face, good. If an opponent blocks, or if our strike runs into his strike, then (I assume you have read my eBooks with Wing Chun techniques and you know that the hand is relaxed, except for the effort to keep it on the central line) it bends, forming either bon sao or gun sao block. But it happens "by itself"! It is a side effect of the strike! Initially our intention was to attack, not to block!

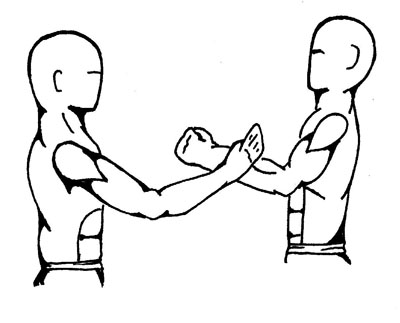

Now, as we performed bon sao, should we retreat? No. The hand bends, while we "always go forward", so now the elbow strikes. Really, what choice do we have? The opponent blocked the fist, and we want the hand to keep going forward. The only part that still can do it is an elbow: wow! We have just figured out a technique!

What is important: on the picture you see an attacker striking his opponent with the elbow. The shoulder JOINT of the striking hand is forward, but the back is not turned; this is an important concept of Wing Chun, we fight in a "square" position, without bringing one shoulder to front. The reason is explained in details later, for now let's just say that moving a shoulder back contradicts to "we never retreat" rule.

And if we did gun sao, we continue (again - forward!) either with the elbow or with the fist. Or with the palm. Or... Does not mater, we go forward.