Wing Chun Kun Fu

Description of techniques

Bon Sao

Being part of Sil Lim Tao, Bon Sao is the "basic" technique, but it is a complex one nevertheless.

First of all, it is not exactly a blocking technique. It is an attack, that - unfortunately - was interrupted by the opponent.

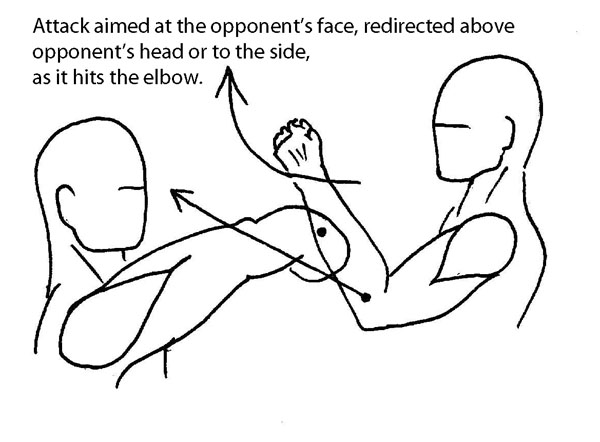

Note a bended arrow near the elbow of a person on the right. This is a trajectory of an elbow. And what would happen, if this elbow moves, uninterrupted? That's right, it will end up striking opponent's neck. Or ear.

This is a very important point about Wing Chun in general, so let me explain. In a full-speed fight (think catfight), there is a very little chance of blocking properly. Punches are just too fast and unpredictable! Different schools have developed different ways of handling this issue. For example, in competition-oriented Kiokushinkai karate, punches in the chest, abdomen and thights are simply ignored, as fighters are sufficiently strong to absorb them.

There is a reason I used the words "competition-oriented". No punches in the head, that's what it is all about. You can ignore (for some time, at least) punches in the body, but it is safe to assume, that the first punch in the head that you cannot deflect will end the fight.

As for Wing Chun, most of punches are directed to opponent's head, as a) it is the most vulnerable area and b) the objective of Wing Chun is to end the fight as fast as possible.

The approach Wing Chun takes is to attack, again, it is a logical spep from the "end the fight as soon as you can" presupposition. You can not end the fight by defending yourself, so - sacrify defence in favor of the attack.

However, if you attack with no defence at all, you will loose - the first counter attack of your opponent will be the last thing you see coming.

A solution is to attack in such a way, that it works as a defence in the same time.

Here goes Bon Sao.

Just think about it: you hit your opponent with your elbow. If it works - you win. If your opponent strikes you with his fist in the same time, the elbow will intercept the fist, so it works as a blocking technique. But originally it was not intended as blocking!

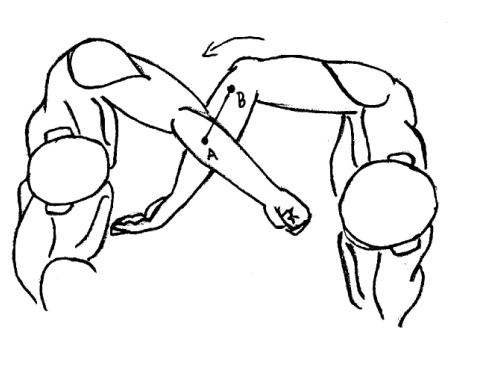

Ok, few words about details. Let's take a look at the picture again.

The elbow strikes towards the opponent's neck. It meets the hand, and stops. This is the first checkpoint: you do not have to move opponent's hand up. Because it is already stopped, and by moving it up you will spend some time and energy.

It does not really mater which part of your forearm contacts with the opponent's hand. You shouldn't think about the forearm at all - you STRIKE WITH THE ELBOW!

This is the second important checkpoint. The forearm is attached to the elbow, so when you move elbow, it moves too. But your attention should be on the elbow.

As the forearm is not that important, it may bent (in the elbow). Of course, it would be nice if your wrist stays at the central line and your hand remains almost straight... it just is not required for the technique to work. Remember - you are not trying to stop opponent's hand dead where it is, as it would take to much strength. You are not trying to lift it as well. So... what is left? Pushing it slightly to the side, away from the central line.

The keyword is "slightly" - just enough to avoid being punched.

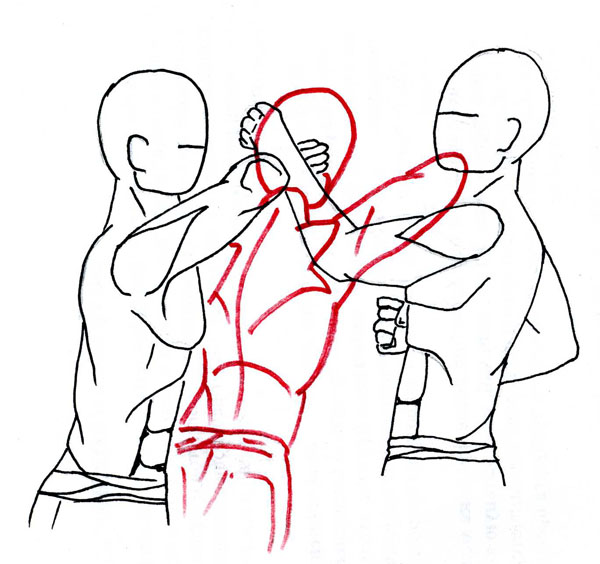

The third important thing to keep in mind. If you push opponent's hand too far away, he will bend his elbow, and attack you - same way you just tried!

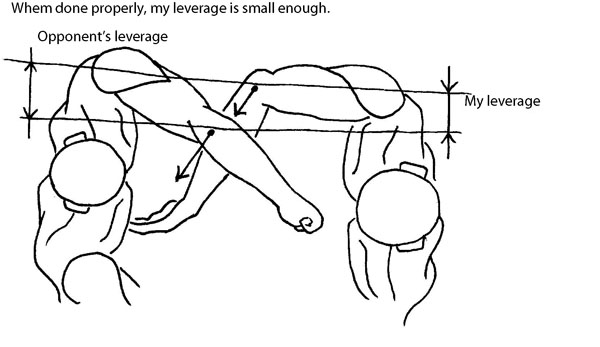

Finally, about the contact point between your hand and the hand of your opponent. It should (if possible) slide from wherever it was the moment your hands meet to the elbow (your elbow). The reason is simple - the leverage is smaller there, so the force you can apply is bigger. Remember - you still strike with your elbow, so - if the hand is on the way - you can use it to take your opponent off balance.

Once again, Bon Sao is all about the elbow. The force, applied to the point, where your hand touches your opponent's hand (the point of contact) is projected from the elbow. Therefore, except for extremities, the angle between the shoulder and the forearm is not important at all.

A useful metaphor, perhaps, to explain some common mistakes: we use our elbow to push against his elbow. What if we don't?

If the force is misaligned, going against the opponent's wrist of middle part of his forearm, he will use the contact point as a pivot point to bend his elbow - and it will go straight at your head.

Another problem arises, if your opponent does not care about your defences, he is strong, and he is using physical power to push his fist through. If you use your wrist, and not elbow, to generate force, it is your triceps against his body weight plus his inertia. Your hand will collapse, period. Of course, you can step to the side, amduse that same elbow to attack your opponent... but the fact is - you have lost the first round, as his fist goes straight to your head, and is going to reach its destination faster, unless you boost your own speed.

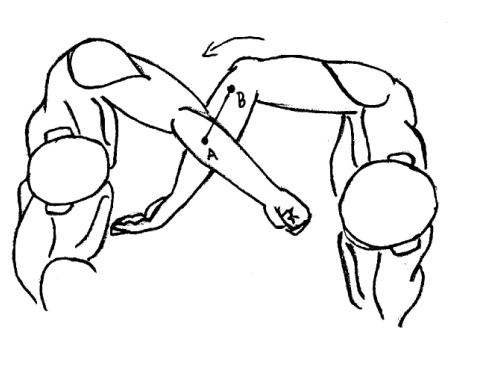

In the same time, if we perform Bon Sao with our hand straight, The elbow (our elbow) does not form a "bump" on a hand, that prevents an opponent from sliding his hand to your shoulder. As soon as he has a hand on your shoulder, he can use two hands to press on your hand while controlling your shoulder. Your hand will form an enormously long leverage, and your muscles will not b strong enough to resist, therefore, you will end up with your hand pressed against your chest, a position where you are totally helpless.

To better understand Bon Sao one can also think about it as about a natural defensive technique. This is just a metaphor, from my personal perspective, as I would rather think in terms of offensive Wing Chun model. But it explains mechanics of the technique.

Say, someone approaches you and you believe he is an agressor. What you do in Wing Chun - the very first thing - is extending your hands in his direction. Placing them between you and your opponent, to make it impossible for him to close the distance.

Now, let's say you are late, and he is already within the striking distance, and he strikes. And - just for the sake of this example - you have your hands in your pockets.

Now, you don't have time to put your - extended - hands between you and your opponent, so you move your elbow up! And you end up with a Bon Sao of a sort.

This particular metaphor about martial arts is called "listening to your fear", and it works fine... Just keep in mind, that there is a difference between "fear" and "defensive", and Wing Chun is not a defensive style.

One question people keep asking is "what if my elbow goes up - outside?" Indeed, you can move your hand around Bon Sao, but a) the punch will be weak, and b) what do you think the hand of your opponent will do, if it does not meet any resistance? That's right, it will strike, and - due to the mechanics of this situation - it will strike FIRST, before your hand finds its way around Bon Sao.

Jeet Kun.

This is not exactly a technique, but rather a concept. The idea is to launch serial strikes by the central line, taking the opponent off balance and forcing him to go defensive.

The elbow in this technique is down, and it should move by the central line as much as possible. Because your striking hand is also an obstacle you place on the way of your opponent's hand, and if you move it off the central line, well... there will be an opening your opponent will use.

Here, as in many other techniques, we strike with our attention on the elbow. The forearm and the fist... Theyare just attached to the elbow, and they move along with it, but still - do not focus on them.

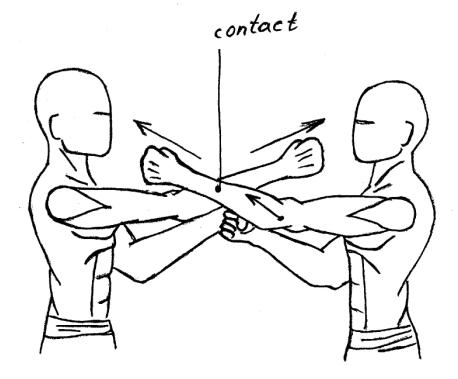

If your hand HAPPENED (it is all at random, it is a catfight!) to be on top of your opponent's hand, it should not become straight. Why? Because if it is straight, your opponent's hand will be able to reach your corpse.

In the same time, if your hand is UNDER opponent's hand, it should go straight. Because if it remains bent, it wouldn't stop opponent's hand from striking you in the face.

These two rules are based on the mechanics of a human body, and you will feel it immediately, if you try it with the pertner. It is also very easy to follow. Let's say you strike, with your attention focused on your elbow, and your hand comes on top of your opponent's hand. Then, as your elbow is down (physiology!), it will hit the opponent's forearm and stop, before the hand becomes straight.

If, however, your hand is below your opponent's hand, it will not be prevented from becoming straight, as the elbow is still DOWN, and there is nothing below your hand for it to hit and stop.

Let me repeat: it all happens naturally, as at the speed of a real fight, you will have no time to think "ok, my hand is on top, I better keep it a bit bended in an elbow joint". No. Elbow down, if it hits an obstacle, it stops, if not - it does not.

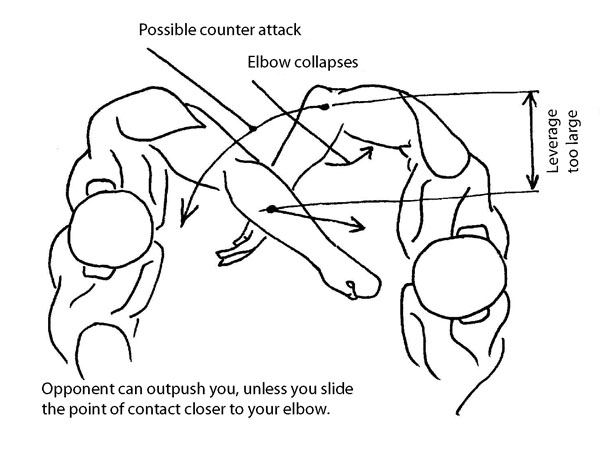

The way hands move is shown on the following picture:

The fist goes forward by the straight line. It is a common mistake to move it in a circle (up - forward - down). A hammer-like strike is not nearly as strong, besides, the main idea is to strike in a way, that lifts your opponent, by putting him on his toes. So the strike should go by the straight - and directed slightly up - line.

Then the fist goes down (away from the striking trajectory of the second hand), and returns to the initial position, in front of a middle chest, and about two fists from the chest bone.